Why Algorithms Won’t Always Control How We Discover Great Art

On seeking a better discovery system for creators and consumers

Whenever a Walmart enters a small town, local retail stores lose nearly half of their trade within a decade, and local employment goes down. Various studies and papers documented this pattern. But in 2006, a book brought the issue further into the national spotlight and cemented the phrase, “The Walmart Effect.”

The Walmart Effect can be simplified into something like this:

Walmart is both the largest retailer and private employer in the United States and most of the world. Because of its size and influence, it can pressure suppliers into selling goods at much lower costs, then sell to consumers at cheaper prices. This forces mom-and-pop shops and regional grocers to either slash their prices to unsustainable levels to compete or shut down entirely. Also, Walmart is estimated to source 60%-80% of its goods from China alone. It usually doesn’t buy from (and, therefore, doesn't support) local shops, manufacturers, and other county-based suppliers. So as local retailers vanish, so does the business they fostered with local suppliers who are gradually replaced by Walmart’s national and international network. More local enterprises close as a result and the money centralizes within Walmart instead of circulating among the residents of that county. It’s no wonder that more people become unemployed in places where a Walmart Supercenter stands, compared to places without. Walmart turns into a “monopsony”: Like a monopoly allows a company to sell goods with exorbitant prices due to a lack of competition, a monopsony allows an employer to pay lower wages because workers have few alternatives.

This phenomenon is very much present in today's creator economy. We are now in a sort of monopsony of algorithms, where a handful of tech giants own the platforms from which we create and consume content. This gives the platforms power to dictate what content and art becomes popular and, consequently, what earns.

We already have quite a number of conversations about how algorithms are turning our culture homogenous. The paradox of the algorithm is that it is designed to be highly personal—it notes the user’s preferences and recommends things that are likely to appeal to that specific user—and yet it’s one of the quickest ways to spread sameness.

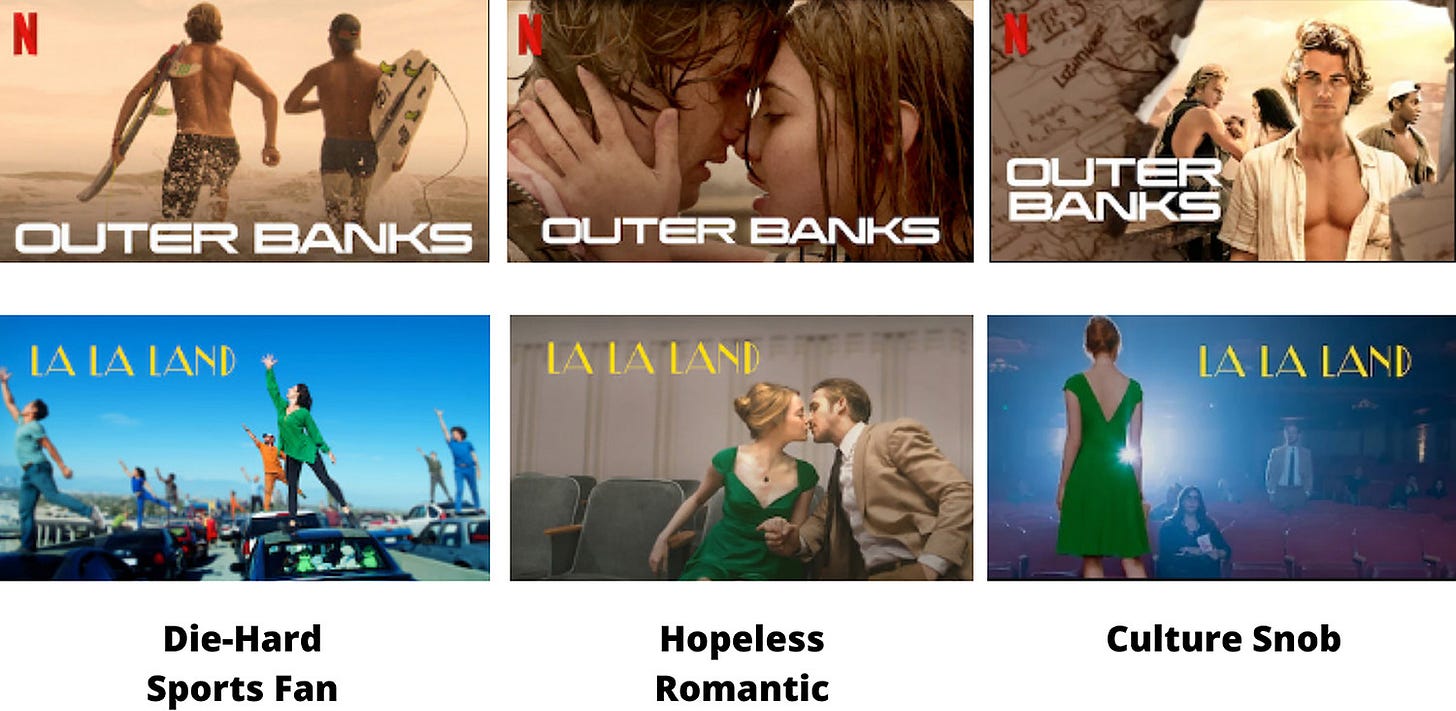

I think a 2021 paper on Netflix’s recommendation system is a great demonstration for why this happens. The paper’s author, communication strategist Niko Pajkovic, aimed to investigate how Netflix’s recommendation systems worked and how it might impact personal taste. He designed a set of fake accounts with different personalities like “The Culture Snob,” “The Die-Hard Sports Fan,” and “The Hopeless Romantic.” These personalities strictly watched shows that corresponded to their profile: The snob only watched arthouse films and obscure foreign directors, while avoiding reality shows; the sports fan only watched shows that featured strenuous physical activity and ignored romantic comedies, and the romantic exclusively watched high drama shows that vary between high and lowbrow. Expectedly, the homepage for each account showed identical shows in the beginning. But that changed as each account started watching shows that corresponded to their “personal taste.” On the fifth day of the experiment, the snob’s account featured a row of “Critically Acclaimed Auteur Cinema,” while “Movies for Hopeless Romantics” dominated the romantic’s recommendations. Two weeks later, each profile appeared highly personalized, with Netflix’s recommendation system seemingly catering to different tastes by offering films aligned with each viewer’s preferences.

At least, that’s how it seemed at first glance.

Over time, Pajkovic noticed something peculiar: Certain shows were recommended to all of the profiles, even if they didn't necessarily match the profile’s taste. For example, the Netflix-produced series Outer Banks is a teen-drama mystery, which the hopeless romantic might like, but I’d guess is unlikely to be enjoyed by the snob and the sports fan. Or La La Land, the musical, which the snob might consider, but I doubt the sports fan would. The catch was that their thumbnails were personalized accordingly. Below are the screenshots of how the shows looked like for each profile.

If I were the sports fan and I had no idea about these shows, I would have thought, at a glance, that Outer Banks is a series about surfing, while La La Land is a film about urban dancers. If I were the hopeless romantic, the former would seem, to me, like a teen love story set on a beach location, and the latter a love story between a 50s-era couple.

A generous take would argue that Netflix’s algorithm broadens horizons by personalizing thumbnails and enticing viewers to explore shows they might normally ignore. A less generous one, however, would suggest that Netflix essentially engineers popularity by force-feeding certain shows to users regardless of their tastes. By altering the presentation of the same content to make it look more similar to a user’s preferences, platforms can manipulate what people are exposed to, thus prioritizing their own agenda and continuing to homogenize culture.

Just as Walmart dictates the limited employment options of the community it occupies, the algorithms decide how art and content should appear, how often they should be published, and what format they should take. In both scenarios, a single dominant player becomes a “one-stop shop,” narrowing the routes through which goods or content can reach us, and effectively reducing the visibility of smaller, independent voices. One of the biggest benefits of a one-stop shop is convenience, but that convenience, in the case of Walmart and platform algorithms, comes at a very steep price.

Workers have little choice but to Walmart’s terms. Creators and artists are forced to bend their work and lifestyle to fit the algorithm’s demands.

This is why “improving” the algorithm isn’t the right solution.

Big tech is inherently structured to prioritize shareholder returns. The journalist and author, Cory Doctorow, describes the pattern well:

“First, they [the platforms] are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves.”

Unless the leadership of the biggest tech companies suddenly becomes much less greedy, the eventual “enshittification” of online platforms is inevitable. Therefore, the long-term goal for creators and consumers is to ensure that algorithms eventually stop being the main deciding agent on what’s worth watching, reading, or listening.

That said, this article isn’t about why algorithms shouldn’t hold this power—it’s about why they won’t.

Something far more powerful existed before the algorithm

It’s hard to imagine something else realistically replacing algorithms. But history allows us to zoom out of our time zone and see a bigger picture. For over a millennia, way before modern social media, something far more powerful dictated what most people could consume: The Catholic Church.

In much of medieval Europe, religious authorities oversaw the publication of texts. If an aspiring writer wanted to produce a work at odds with Church doctrine, or simply without clerical endorsement, the writer risked accusations of heresy and worse. In the 14th century, for example, the Catholic priest and University of Oxford professor, John Wycliffe, earned the ire of the papacy for, among other things, his translations of the Latin bible into Middle English (though some scholars challenge this). At the time, only the elite and the clergy were educated in Latin. So Wycliffe’s translations allowed the laity—the ordinary people and worshippers—to read the bible directly and form their own opinions and interpretations of it, instead of relying on the preachings of the clergy, as was the status quo. The Church wanted Wycliffe excommunicated, maybe even executed, but the professor had powerful patrons and supporters among the nobility. So The Church contented itself with burning Wycliffe’s translations, including his other works, pronouncing him a heretic, and, later, exhuming his remains. Other figures faced even harsher penalties. In the 16th century, the linguist and scholar William Tyndale was executed for his Bible translations, while the poet and cosmological theorist Giordano Bruno was stripped naked, his tongue clamped “because of his wicked words,” and then burned alive at a stake for proposing that the stars were distant suns surrounded by their own planets and possibly fostering life of their own, among other “heretic” ideas. There were, of course, a number of notable individuals who circumvented The Church’s dominion at the time: Niccolò Machiavelli authored The Prince and Christine De Pizan earned her living solely through writing, and became “the first professional woman of letters in Europe.” Neither faced documented punishment for their works during their lifetime (though the Church later banned The Prince after Machiavelli’s death). Various factors contributed to their success, but a key distinction lies in a consistent pattern: these artists and thinkers thrived by securing the patronage and protection of powerful aristocrats. In an era when literacy and intellectual exchange were exclusive privileges of the wealthy, artists without personal wealth had little choice but to depend on the favors of nobles.

This system of aristocratic patronage began to evolve with the advent of the printing press in the mid-15th century. Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of movable type revolutionized how information was disseminated. For the first time, texts could be reproduced en masse, and ideas, radical or otherwise, could reach a relatively broader audience.

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses, which helped spark the Protestant Reformation against the Catholic Church, and the physician Andreas Vesalius’s De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem (On the Factory of the Human Body in Seven Books), which challenged the time’s medical dogma, were products of this technological shift. Though the Church banned or condemned works like these, the printing press ensured their survival, paving the way for intellectual freedom.

As more people accessed information, the Church’s almost absolute control over knowledge and culture began to decline. The Renaissance flourished and aristocratic patronage still played a role, but something was changing. Artists began finding an emerging marketplace of growingly literate individuals outside of the nobility: Merchants and urban elites began to commission and purchase more artistic work, including literature.

By the 1700s, a vibrant culture of ideas took root in bustling coffeehouses and salons across London, Paris, and Vienna, where pamphlets and political satires circulated and ignited public debate. The 1800s Industrial Revolution then slashed printing costs, turning newspapers and cheap books into major engines of discovery: Charles Dickens and his contemporaries quickly found mass audiences, and publishing houses rose to power as gatekeepers. Yet, even as mainstream publishers shaped cultural taste, small presses and literary societies remained to champion works that big establishments overlooked.

A hundred years later, in 1929, commentators lamented the death of critical thinking, and, indirectly, reading—all because of the entry of this new technology called the radio. Instead of trying to avoid awkward silences by participating in the “art of conversation,” people could now simply turn on the radio and let a stranger’s voice fill in the silence. Then television came. Then the first console games. Now, after almost another hundred years, pundits continue to talk about the death of reading and critical thinking. In one aspect, they’re right: Since people have more entertainment options other than reading or quiet introspection (unlike in pre-radio times), there are fewer readers now. Yet here we all are. Readers and lovers of great art have always found ways to keep it alive. Despite the dominance of publishing houses, then radio, and later TV, alternative movements emerged: Beat poets in 1950s America published affordable chapbooks, and underground zines thrived in music and political circles.

The most astonishing thing, though, is the timeline.

The Church arguably dominated Europe for a thousand years while traditional publishers held one of the highest gatekeeping and curation powers for approximately half that. Then online technology, starting from the widespread adoption of the internet in the 1990s, disrupted these two authorities by taking almost absolute control of people’s attention in just 20 years.

In parallel with computer scientist Ray Kurzweil’s Law of Accelerating Returns—a concept that observes the rate of technological progress increases exponentially over time—each new era of innovation happens faster than the last, compressing the time it takes for an incumbent power to be disrupted. Put simply, because technology improves at an accelerating pace, information and tools become more widely accessible in shorter spans of time, which reduces the duration any single institution can maintain near-absolute dominance. Entities that once controlled information or technology for centuries now find their dominance unraveling within mere decades.

All of these shifts point to an underlying historical pattern: each era’s dominant platform eventually finds itself eroded or co-opted by something newer. The Church no longer decides who publishes, the traditional publishing gatekeepers have had to share space with digital platforms, and radio and television have been joined by infinite streams of online content. If there is one lesson from this long arc of cultural history, it’s that no system of discovery, however entrenched it appears at the height of its power, has remained the final word on what people get to consume.

In fact, we’re already seeing the cracks as early as now, when mainstream usage of ChatGPT and generative AI is only barely three years old. Audiences are starting to show hunger for substantive, reflective experiences. Simply take a look at the most popular podcasts and you’ll see two to four-hour episodes racking millions of views and listens. Substack newsletters, where writers can explore nuanced ideas in long-form writing, are thriving. (Fashion enthusiasts and shoppers, who are usually found on TikTok and Reels, are reportedly flocking to Substack in search of personal recommendations that defy the sameness of styles offered by the video-first platforms). In-depth video essays on YouTube continue to build a dedicated fanbase. Meanwhile, readers become increasingly wary of AI-generated writing, and some even seek out creators who specifically do NOT use AI in their personal work.

Whenever new gatekeepers emerge, counter-movements inevitably surface to champion a different, more meaningful, and diverse way of engaging with art and ideas.

Entrepreneurs often like to credit technological advances for driving major social and cultural changes like these, but I believe the bigger credit lies with grassroots efforts to build parallel systems that challenge the “monopsonies” of different eras: The zines, the salons, the small press publishers, the indie creators and artists. Of course, none of these efforts would survive or thrive without the enthusiastic support of their audiences. A single article from some obscure Substack newsletter might not topple the empire of algorithms, but collectively, independent works form a powerful counterweight to mass-produced content.

Just as people no longer rely on the Catholic Church for information and art, despite Catholicism still being one of the largest religions in the world, I can imagine a future where algorithms are everywhere, yet no longer the dominant power in discovery and curation.

Ultimately, it is up to us—the supporters of independent artists, the subscribers of long-form writers, the patrons and creators of authentic art and nuanced exchange—to nurture these ripples until they grow into the next great wave. Algorithms, just like their predecessors, will be replaced by a better, more equitable system as long as we continue the collective effort to make it so.

See if this newsletter is for you. Learn what you can get out of Artist Analysis here.

The insight about Netflix disguising the same show with different thumbnails for each user hit me hard. I once clicked on a movie simply because the poster featured a musical note, assuming it was about jazz only to discover it was a teen romance. It was such a bizarre experience and it reminded me how my streaming platform seems to know exactly which “visual cues” I’ll fall for. It’s both fascinating and unnerving to realize how easily we can be nudged toward watching something we’d normally skip.

It’s comforting to imagine that the search for depth - real depth - is as timeless as art itself.

There’s something poetic about the idea that, no matter how algorithms homogenize our culture, there will always be a counter-current.

I’ve always felt drawn to spaces that thrive in spite of systems, like tiny bookstores or niche blogs, and I can’t help but believe that these small rebellions are where the soul of art continues to breathe.